Exploration and discovery of Madadagascar by writers

Etienne de Flacourt (1607-1660)

Etienne de Flacourt headed the French settlement of Fort-Dauphin from 1648 to 1655.

As governor of Fort-Dauphin contributed to the colonization of the Bourbon Island (now Reunion) and to the knowledge of Madagascar and Bourbon Island.

In 1653, he included in his "History of the Great Island of Madagascar" the account of the mutineers he had banished to Mascareigne.

In 1658, he added the report of the stay of some Frenchmen in the company of Malagasy people.

He will also, according to them, create a map of Bourbon.

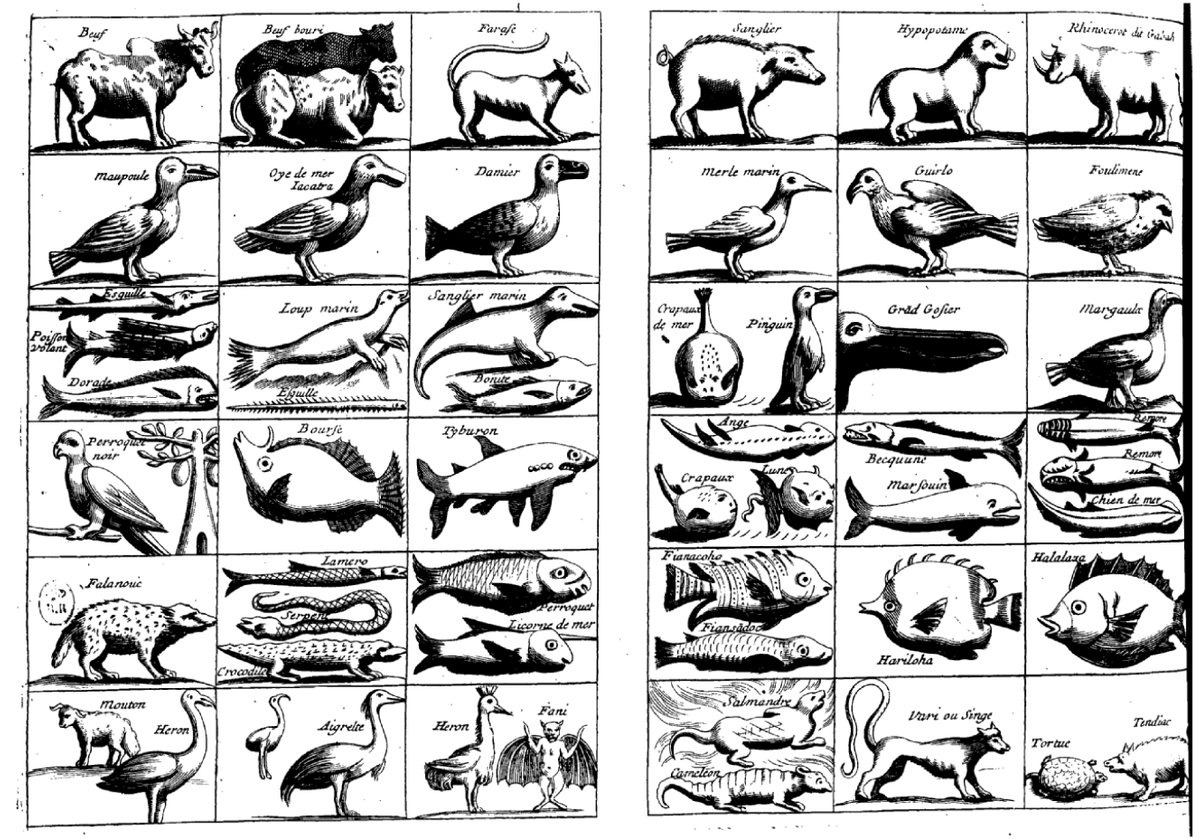

If he failed in his trade mission, he left several works, including a dictionary of the language of Madagascar and a history of the Great Island of Madagascar, which are very well documented and richly illustrated.

Here is one of the first pages of this true sum, which introduces the southeast of the island, its fauna and flora, the history and customs of its people.

There are a lot of animals

The "St. Lawrence Island" is called Madagascar by geographers, by the inhabitants of the Madecasse country, by Ptolomeo Memuthias, by Pliny Cerne, by the author of the Nubian Geography, by the Persians and the Arabs Sanrandib. But its real name is Madecasse [...].

This island is one of the largest in the world, filled with fertile mountains of forests, pastures and plantations and a landscape watered by rivers and ponds full of fish. It feeds an infinite number of oxen, very different from those in Europe, all of which have a certain lump of fat in the shape of a magnifying glass on their backs.

This has led some authors to say that she feeds camels [...].

There are few animals that are harmful to humans and livestock. In the forests there are wild boars, which are different from those in Europe and less dangerous. They are very hideous to look at, having two horns under both eyes, covered with skin and not higher than an inch [...].

There are a large number of animals, birds and fish that I will describe below, each in its own place, as well as many plants and rarities.

Etienne de Flacourt, Histoire de la Grande Île Madagascar, 1648-1655,

Karthala, Paris, 1995

________________________________________

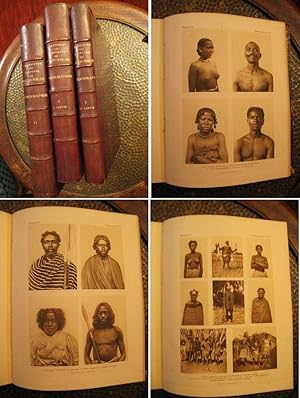

Alfred Grandidier

The Lorraine Alfred Grandidier (1836-1921) traversed the island between 1864 and 1875 and in turn became a naturalist, geographer, ethnologist, historian and chronicler.

The N

However, it was a malaria crisis fought in India, his major exploration project, that forced him to change his plans.

He went to Reunion Island to recuperate, but was soon attracted to Madagascar, a vast territory still little traveled by Europeans in the 1860s.

After returning to France, he devoted the rest of his life to a monumental physical, natural, and political history of Madagascar - an encyclopedic work continued by his son Guillaume (1873-1957).

In 1868, while collecting specimens of Malagasy flora and fauna, Alfred Grandidier discovered two subfossil animals that were still unknown to scientists.

The rock bird

In Ambohisatranà I stopped to cook my lunch and I was visited by the chef of the place, with whom I talk about the products and especially about the animals of the land [...] especially the song'aomby (litt. "that resembles an ox"), and when I asked him about this animal [...] he showed me a pond near my stop and told me that there were some bones.

Enthusiastically I went into the water, and with some of my men we began to search the mud that lined the bottom of the pond, and I removed some other bones of the giant bird, the Aepyornis, still known only by its eight-liter eggs and some indefinable debris [...]; with these bones were many others belonging to a still unknown species of hippopotamus, which I named Hippopotamus lemerlei in honor of our Tulear factotum, and to other new and interesting animals.

Alfred Grandidier, Reiseandenken 1865-1870,

Publication of the Malagasy Society of Archaeology, Antananarivo.

________________________________________

James Sibree

James Sibree was born in Hull on April 14, 1836.

In his early life, Sibree served as a student engineer and worked for the Hull Board of Health (1859-1863).

In 1863, he sailed to Madagascar after being appointed architect of the Memorial Churches, Tananarive, for the London Missionary Society (LMS).

He worked at the churches in Ambatonakanga, Ambohipotsy, Andohalo and Manjakaray. In 1867 he returned to England to study at Spring Hill College, Moseley, near Birmingham.

James Sibree was ordained to the priesthood in 1870. In February of the same year he was also married to Deborah Richardson.

Together with his wife, he returned to Madagascar as a missionary and was stationed in Ambohimanga.

He worked on a revision of the Malagasy Bible, participated in a deputation, and went to work at the Theological Institution in Tananarive in 1876.

He worked in Antananarivo for four years as the architect of the Protestant churches and made several other visits to the Big Island.

In Madagascar and its Inhabitants, both travel diary and compilation work, he gives his first impressions of the country.

From the coast to the highlands

Wednesday, October 7 - We were up early and left our quarters at six o'clock on a beautiful morning. We had to climb hills again, go down valleys and pass many rivers, with the only difference that the hills became higher and steeper, the path more difficult [...].

On the way, we encountered a large number of maromitas transporting poultry, cassava, potatoes, rice and other products from the interior to the coast. Most of these items are transported to Tamatave or another port so that merchant ships can be supplied abundantly and at very low cost.

Poultry is transported in woven cages with poles made of bamboo or other light wood. We also passed several people loaded with European products for the capital, such as cheap pottery, iron cooking utensils, and a variety of other items.

Others carried salt, others wicker baskets filled with the raw fibers of the raffia palm, believed to be so abundant on the coast; it was shipped to Tananarive and other inland places to be used in the manufacture of fabrics.

These men were sometimes isolated or went in pairs or threes, but most often they traveled in groups of

... When I toured this region, I could only be impressed by the richness of the land and the immense resources it would offer to production if properly harnessed by the culture.

The hills would serve as pasture for millions of cattle, the valleys would grow sugar, rice, and coffee in sufficient quantities for consumption by the entire British Empire, and the coast would be ideal for growing cotton.

The country is also rich in minerals, copper, iron, and in the northern part probably coal.

James Sibree, Madagascar and its people: diary of a four-year stay on the island,

Trad. H. Monod, Société des livres religieux, Paris, 1873.